Collection

The Seikado Collection

Our museum focuses on special, thematic exhibitions and does not have a permanent exhibition space.

Seikado houses their collection of 6,500 works of art in a museum.

Yanosuke Iwasaki collected a wide range of art including swords, tea ceremony utensils, Chinese and Japanese painting, calligraphy, pottery, lacquerware, paper and brushes, and wood carvings.

His son, Koyata subsequently expanded the collection, pouring his soul into establishing a comprehensive and systematic collection of Chinese pottery and porcelain covering the Han through Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties.

National Treasure

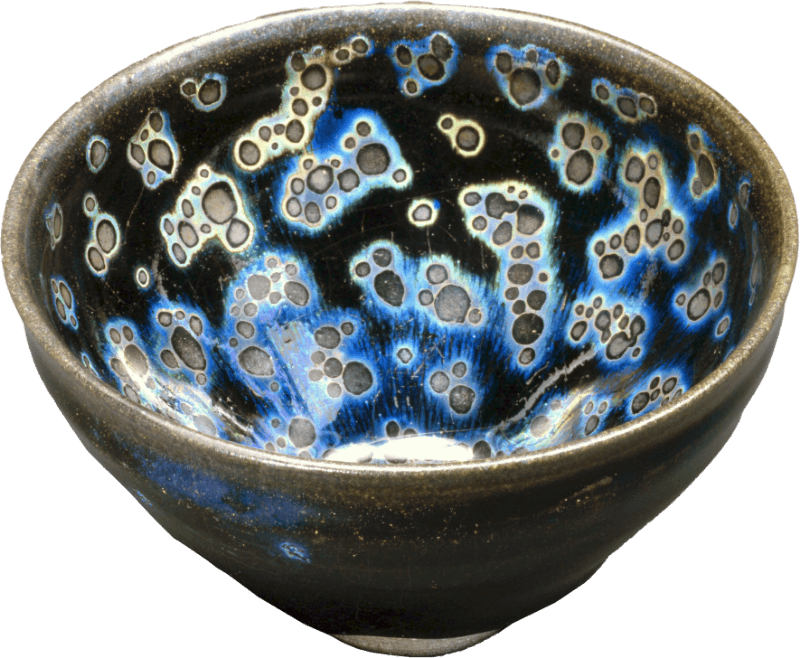

Tea bowl, Yōhen Tenmoku, Jian ware

Known as “Inaba Tenmoku”

Southern Song dynasty, 12th-13th century

Regarded as the most precious among Tenmoku (black glazed) type tea bowls, Yōhen (iridescent spotted) Tenmoku are a kind of black glazed tea bowls with its inside surface covered with many spots surrounded by deep blue radiance. There are only three tea bowls of this kind that are known to exist. This piece has the most vivid luster and a finely chiseled foot. Recently (2009) fragments of yōhen tenmoku were excavated for the first time in China, from the site of Imperial guesthouse in Lin’an (Hangzhou), the capital of the Southern song dynasty, and drew people’s attention. This tea bowl, as indicated by its alias “Inaba Tenmoku”, was preserved for many generations by the Inaba family, who later ruled Yodo fief (part of Kyoto city), during the Edo period. It came into the possession of the Iwasaki family in 1934, but Iwasaki Koyata never used it, saying “The treasure of the country must not be used privately”.

Yōhen tenmoku are all in Japan and designated by the government as national treasures. The other two pieces are owned by Ryōkoin, a subtemple of Daitokuji in Kyoto and Fujita Museum of Art in Osaka.

National Treasure

Tachi sword, signed “Kanenaga”

accompanied by sword mounting of itomaki-no-tachi type, with scabbard decorated with chrysanthemum and paulownia-embleme design in maki-e lacquer

By Tegai Kanenaga

Kamakura period, 13th century

Japanese swords have a history spanning 1000 years, in which they were regarded as a symbol of militaristic power as well objects of artistic appreciation. The points of appreciation can be roughly divided into three categories; the shape of sword with curvature, blade surface texture resulting from forging, and wavy edge patterns formed by the structure of hard steel resulting from tempering.

The maker of this sword, Kanenaga I was the founder of the Yamato Tegai school who was active around the Shouō era (1288-93). Calling himself Tegai Heizaburō, he is said to have lived in the neighborhood of Tengaimon gate of Tōdaiji temple in Nara. The Tegai school was the largest of the Five schools of swordsmith in Nara( Senjuin, Tegai, Taima, Hōshō and Shikkake)and continued to prosper as Monju school in the Edo period.

This sword is high-ridged and deeply curved, and characterized by straight grain surface texture and straight edge pattern mixed with a variety of wavy patterns. It is a representative work from Yamato area, still intact after 700-odd years of its production.

National Treasure

Scenes from Sekiya (The Barrier Gate) and Miotsukushi (Channel Markers) chapters of The Tale of Genji

By Tawaraya Sōtatsu

Edo period, 1631

Pair of six-fold screens, color on gold-leafed paper

Tawaraya Sōtatsu (dates unknown) was an early Edo period painter in Kyoto, who created a style which was inherited later by Ogata Kōrin, Sakai Hōitsu and others who are collectively known today as the Rinpa school. The Scenes from the Sekiya and Miotsukushi chapters of the Tale of Genji is one of the three works produced by Sōtatsu which are registered as national treasures.

This work is recognized as one of his representative works showing the bold composition properly using straight and curved lines, clever use of green, white and other colors, borrowing of motifs form ancient paintings which are the unique charms of Sōtasu’s paintings. This work is thought to have been donated to Daigoji, an old and distinguished Buddhist temple, in 1631. In 1896 the temple presented it to the Iwasaki family as a token of gratitude for the donation Iwasaki Yanosuke made.

National Treasure

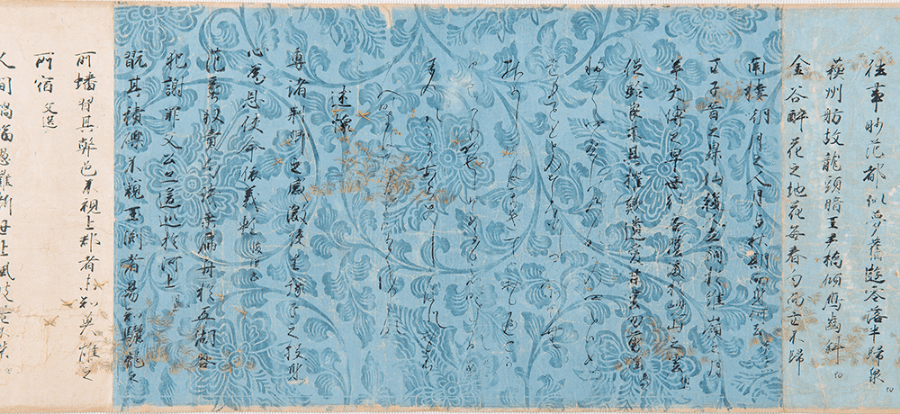

Wakan Rōei Shō poetry anthology : Ōta-gire segments

Heian period, 11th century

Two handscrolls, ink on paper

Written in neat Chinese characters and varied and flowing kana letters, this copy of Wakan Rōei Shū, a poetry anthology compiled by Fujiwara no Kintō, is famous as an excellent work dating from the Heian period.

The blue, light blue, pale yellow and white paper with block-printed patterns is further decorated with flowers, birds, eulalia, etc. delicately painted in gold and silver. The use of paper imported from China and harmony of fine calligraphy and gold and silver painting give this work a rare quality that can hardly be seen in other extant examples. Showing the refined aesthetic sense of the Heian period, this anthology is known as “Ōta-gire”(Ōta segments) as it was formerly in the possession of the Ōta family which ruled the Kakegawa fief during the Edo period.

Important Cultural Property

Drum-shaped tea ceremony fresh water jar with celadon glaze and applied peony design, Longquan ware

Southern Song-Yuan dynasty, 13th-14th century

One of the masterpieces of Longquan celadon wares, this ceramic vessel was preserved as a fresh water jar used in the tea ceremony by the Kōnoike family, wealthy merchants in Ōsaka. Because of the rounded body and the ornament resembling rivets near the rim and base, it was named “drum shell water jar”. Excepting the underside, the jar is covered with bluish celadon glaze called by tea masters “kinuta type”.

The glaze on the inside of the jar is exceptionally beautiful. Under the glaze is a decorative design of peony flowers and leaves carefully made of clay in molds and vines made of clay ropes, which are applied on the body surface in an arabesque style. This design is known as “raised peonies”. The lid is also decorated with raised peonies design and the knob is in the shape of pistil and stamen.

Important Cultural Property

Narrative picture scroll of the Heiji Civil War: Scroll of Shinzei

Kamakura period, 13th century

Handscroll, color on paper

Heiji civil war, which occurred in 1159, was a coup d’etat effected by Fujiwara Nobuyori and Minamoto Yoshitomo against Shinzei, a close retainer of the retired emperor Goshirakawa.

Narrating Shinzei’s last moment, the Scroll of Shinzei consists of three sections of text and four sections of illustration. Attacked by Fujiwara Nobuyori and Minamoto Yoshitomo, Shinzei killed himself. His head was severed, paraded through the streets and exposed in public. For its lively depiction of figures, orderly composition, dynamic and forceful brushwork as well as arms and armor showing carefully rendered details, this work well deserves to be called a masterpiece of narrative picture scrolls of war stories.

This precious work is one of three scrolls that presently exist (in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Tokyo National Museum and Seikado Bunko Art Museum).

Important Cultural Property

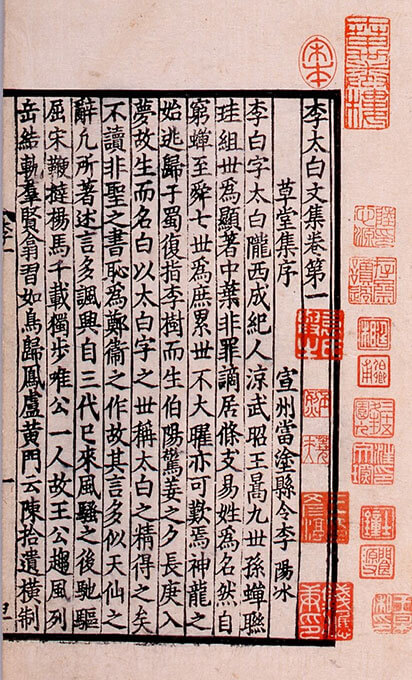

Li Taibai Wenji

(Collected literary works by Li Taibai)

Authored by Li Taibai

Published in very early part of the Southern Song dynasty, 12th century

30 vols. with 1 vol. of general table of contents in 12 books

This is a collection of poems and other literary works by Li Bai (701-62) of the High Tang dynasty. Li Bai is sometimes called “immortal poet”.

Thought to have been published in Shu (present Sichuan province) during very early part of the Southern song dynasty, this set of books is the oldest extant edition of Li Taibai Wenji. The shapely characters have been carved skillfully. The books bear more than forty ownership stamps from various period. They were in the possession of Lu Xinyuan (1834-94), one of the four outstanding book collectors in the late Qing dynasty. Lu Xinyuan is known to have collected important books published in the Song and Yuan dynasties. Iwasaki Yanosuke, the founder of the Seikado Foundation, purchased the entire collection of Lu in 1907, after he died.

Important Cultural Property

Writing box with design from the poem “Suminoe no ….”

By Ogata Kōrin

Edo period, 18th century

The vaulted cover gives an ingenious shape to this writing box. The design covering the entire box features waves washing the shore. The waves have been rendered in plain gold maki-e lacquer, and the rocks on the shore are made of lead plates over which cutout silver characters are embedded. These characters are from a poem by Fujiwara Toshiyuki about little waves lapping at the shore of Suminoe and the lover who tries to hide his love affair. However, the characters represented here do not include those for “shore” and “waves”. Instead, they are indicated by the design. This is a technique called uta-e (poem picture).

This box is a copy of a writing box with a maki-e design by Hon’ami Kōetsu (1558-1637). Following Kōetsu’s design, Kōrin added his original expression to details. This is one of the best works of Kōrin’s maki-e art.

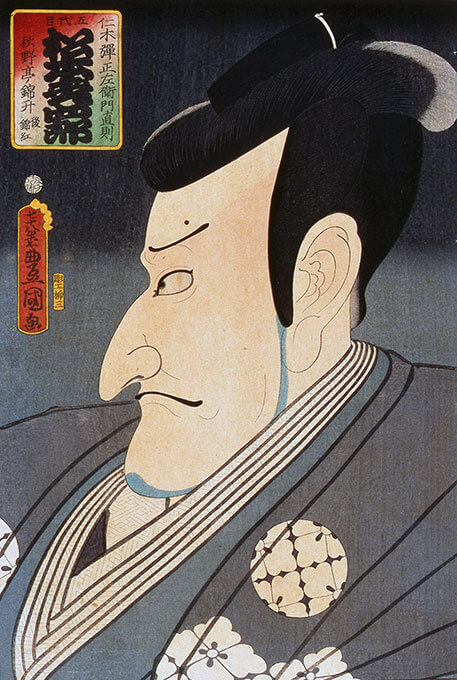

Actor Matsumoto Kōshirō V as Nikki Danjōzaemon Naonori

By Utagawa Kunisada (Utagawa Toyokuni III)

Edo period, 1863

Polychrome woodblock print

This print is one of a famous series of ōkubi-e (bust portrait) of kabuki actors published by Kinshōdō (Ebisuya Shōshichi). A gorgeous collection of works from Utagawa Toyokuni Ⅲ’s final years, it includes a total of 60 prints published over 5 years from 1860. The works, produced using thicker sheets of paper and employing the best engraving and printing techniques was ordered by the Mitsuya family who ran a copper and iron store at Kanda Nushichō.

This print depicts the actor Matsumoto Kōshirō V (1764-1838), who was nicknamed “Big nose Kōshirō” for the peculiar feature of his face, as Nikki Danjō, which was his most successful role. The portrait shows the actor in a mie pose, which was his forte. Successfully expressing the impact of Kōshirō V’s profile as he takes his favorite pose, this is one of the best works among the series.

Tea caddy in nasu (eggplant) shape Known as “Tsukumo-nasu” Karamono (Chinese) ware

Southern Song – Yuan dynasty, 13th-14th century

Boasting a long history of ownership from Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (1358-1408), this ō-meibutsu tea caddy was once owned by the warlord Matsunaga Hisahide. When he presented the tea caddy to Oda Nobunaga, he is said to have been allowed to keep Yamato province in return. It was highly evaluated in various records of tea ceremonies. The name is said to derive from tsukumogami (deities believed to reside in aged objects) or the poem included in The Tales of Ise about an aged woman with white hair (tsukumo-gami). It was damaged when Nobunaga was attacked at the Honnōji temple, and largely broken again when the Toyotomi clan was destroyed during the Siege of Osaka (1615). Ieyasu ordered the lacquer artist Fujishige Tōgen and his son Tōgon to find the tea caddy from the ruins of theŌsaka castle. They found the fragmented tea caddy and restored to the present state using lacquer. Because their repair work was so excellent, Ieyasu gave the tea caddy together with another tea caddy “Matsumoto nasu” (Jōō nasu) to the Fujishige Tōgen and his son Tōgon. In 1885 Iwasaki Yanosuke bought the tea caddy getting an advance on his year-end salary. It was the first tea ceremony utensil to come into the Seikado collection.

Sancai glazed figure of a horse biting its foot

Tang dynasty, 7th-8th century

This sancai (three colored) glazed figure depicts a black horse lowering its head to bite its hoof. Horses, which were craved and taken loving care of by kings and nobles were portrayed in clay and buried in tombs to be remembered in the afterworld. The black color of the skin was created by brown glaze applied over iron slip. With the mane and tail well groomed, this horse has gorgeous saddlery. Yellow-brown leather straps of the headstall and around the neck are decorated with large green tassels and large flower shaped medallions with brown and green glaze are attached to the crupper. The depiction of the saddle cover, which is made either of carpet or animal fur, is very detailed down to its long pile or hair. This sancai glazed figure of excellent Arabian horse reflects the active exchange between Tang and the Western region as well as the lavish life of aristocrats in the High Tang period.

E-tekagami (Picture Album)

By Sakai Hōitsu

Edo period, 19th century

Album with 72 paintings, color or ink on paper or silk

This E-tekagami (Picture Album) consisting of 72 paintings clearly demonstrates that Hōitsu learned diverse painting styles including the Kanō, Tosa, Maruyama Shijō as well as Chinese painting, in addition to Kōrin’s style. The album is accompanied by an inner box with an inscription by Hōitsu himself and an outer box prepared by Sakai Dōitsu (who admired Hōitsu’s style and inherited Hōitsu’s studio Ugean as the fourth generation master), and the binding of the album is thought to be original. The works included in the album show a wide variety, ranging from a painting based on works from Genpoyōka (an album of woodblock prints by Itō Jakuchū) and courtly figures of ancient times reflecting the “taste in classical paintings” which was in fashion at the time, to a simple and unrestrained style work like haiga. This is a precious album filled with Hōtisu’s various charms.